“My research activities concerning the Second World War started in the second half of the 1970s. Professor Ivo Schöffer, my Ph.D supervisor, invited me to speak about the Netherlands and the Second World War at an Anglo-Dutch historical conference on the theme ‘War and Society.’”

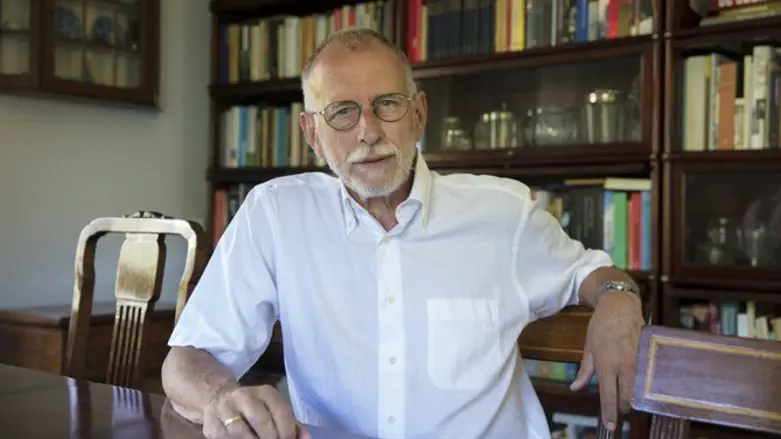

Hans Blom, a prominent Dutch historian, was born in 1943 in Leiden, He has lived there for almost his entire life. He studied history at the University there and received his PhD in 1975. In 1983 Blom was appointed Professor of Dutch History at Amsterdam University. From 1996-2007, he was also serving as director of the Dutch Institute for War Documentation (NIOD).

At the time there was great unease in the Netherlands about the fact that Pieter Menten, a major Dutch war criminal, who had murdered Poles and Jews, led a comfortable post-war life in the Netherlands. Blom says: “At the end of 1976 Schöffer asked me to join a commission of inquiry concerning Menten. The question was how he got away with his war crimes so long in the post-war Netherlands. Why hadn’t there been a criminal investigation? In the detailed reconstruction of what happened, it was discovered how complex – and partly incidental – matters occur in reality.”

In his inaugural address as professor, Blom pleaded for a new approach to the study of the Netherlands during the German occupation. He admired the work of Loe de Jong, then the major Dutch historian in that area and said that his work was full of facts, wide ranging, and easily accessible.

Blom considered that Dutch historians injected many moral and political judgments into their studies of the war period in regard to who was good and who was bad. He said that the role of historians was to be neutral and to understand people in their historical context.

Blom says: “I claimed that continuing research should have new academic angles and questions. There should be more accent on analysis, explanation, and understanding of reconstructed historical events. As examples I mentioned research of the changing mood of the population during the occupation, international comparative research into the results of the persecution of the Jews, and placement of the occupation in a longer historical perspective.”

Shortly before Blom became director of NIOD in 1996, the government asked him whether the Institute was willing to investigate the historical role of the Netherlands in the protection and fall of the Bosnian town Srebrenica and the consecutive mass murders of Muslims there by Bosnian Serbs in 1995. After intense deliberations NIOD took this research on under his leadership.

In 1997, Blom also became a member of the Van Kemenade commission which investigated the Dutch post-war restitution of stolen assets. He soon afterwards became the head of a project of historical research into the immediate post-war period.

Blom was one of the three editors of a major book on the history of the Jews in the Netherlands, which appeared in 1995. After the Dutch edition, it also appeared in English. It followed the periodic congresses covering the history of the Jews in the Netherlands that started in the 1980s.

After his two co-editors passed away, Blom took the initiative for a new edition with additional editors. That book appeared in 2017. Some of the authors were new and several rewrote their chapters.

“We asked the authors to include the results of concrete new research as well as the more theoretical discussions in recent international historiography, such as the economic turn in Jewish history. In particular, we asked the authors, in addition to the original central issue of the history of the Jews as a minority in Dutch society, to analyze the position of the Jews in the Netherlands in an international Jewish context.”

When Blom is asked about the Dutch inability to confront its own history concerning issues such as its failures in the war-time persecution of the Jews, and the many crimes it committed during the decolonization wars in Indonesia, he says: “The Netherlands is a country where the need to make compromises was present very intensely early in its history."

“In addition one can say that the Netherlands in the 19th and 20th century has developed a tradition to think that ‘we’ are a country with very high moral standards. In the 19th century it became unavoidably clear that the powerful Netherlands of the Republic of the United Netherlands was no longer a significant factor. This, despite the fact that we still kept our colonies for a century and half. In these small Netherlands a self-image emerged that it is nicer to be the world’s most moral nation, rather than the most powerful.

“In those circumstances, this attitude was also in line with Dutch interests. As a small country, one has to gain much by peace arrangements and international law. Thus, one, to a certain extent, protects oneself against the desire for power of the big countries. In such a tradition of high moral self-image, it is more difficult to publicly and properly treat events where that is evidently not the case.”