"Even before the Anschluss, Austrians had the Nazi symbol hidden under their lapels," says Marko Feingold, the oldest living Austrian survivor of the Holocaust.

"Anschluss" was the annexation of Austria and its integration into Nazi Germany, which occurred on March 12, 1938.

Almost 105 years old, he shared with AFP his sometimes startling memories of Hitler's takeover of Austria in March 1938 and how anti-Semitism lingered on well after the war.

"Anti-Semitism was already very much in evidence in the 1920s," he says.

"But [Austro-fascist chancellors of the 1930s] Dollfuss and Schuschnigg created such poverty that 80 percent of Austrians welcomed the Anschluss," the centenarian Jewish community leader in the city of Salzburg recalls.

Feingold had moved to Italy in the 1930s to escape that poverty. But he happened to find himself back in Vienna when, on March 13 1938, German troops made their triumphant entry into the Austrian capital.

He was 24 years old and admits to having "no idea" of the true nature of what was afoot, as Vienna celebrated the Nazis' arrival in a carnival atmosphere.

But reality soon hit home. "They say it was Germany which occupied Austria. But it was the Austrian women who occupied the Germans - every soldier had women throwing themselves at him."

Feingold's situation quickly worsened. "The Gestapo came to arrest our father, he was on a pre-prepared list as he was suspected of political activity. Since he wasn't there they took me and my brother away."

The brothers were "beaten for five days" and later released with orders to leave the country immediately.

They traveled to several places before being arrested again in Prague and deported to Auschwitz in 1940.

"At that time, the train tracks stopped two kilometers short of the camp. We had to walk the last part of the way, being beaten by the SS.

"They said I had three months to live. And in fact after two and a half months I was about to succumb to exhaustion when I managed to get transferred to the Neuengamme camp."

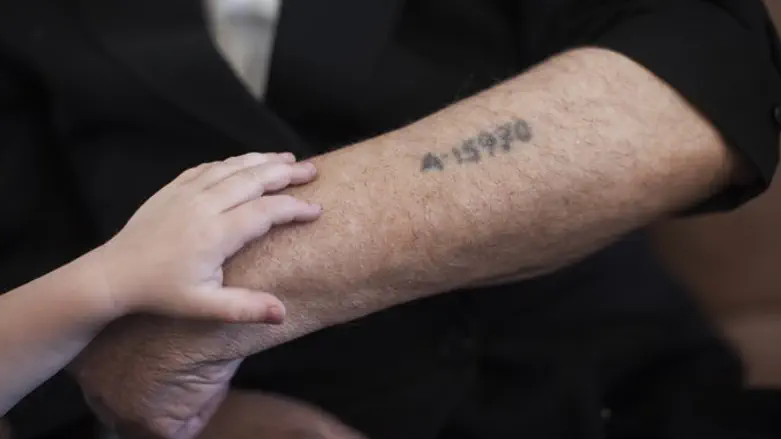

From there, Feingold - or inmate 11,996 - was taken to Dachau and then on to Buchenwald where he survived as a construction worker.

But the camp's liberation in April 1945 didn't bring a quick return to Vienna. "There were people from 28 countries in the camp. Everyone was able to leave apart from the Austrians, they had to stay in Buchenwald until May," he recalls.

When he did try to return to Vienna, along with 127 other survivors, he was faced with another bitter disappointment: no travel allowed through the Soviet occupation zone which surrounded the city.

"A Russian soldier told us that they had orders not to let us pass. The new (social democratic) chancellor Karl Renner had said: 'We won't take back the Jews'," Feingold says.

Having lost his father and siblings in the camps, Feingold went to Salzburg near the German border, which was in the American occupation zone. There he founded a network which helped 100,000 Jews to emigrate to Palestine.

"We had to scheme to get around the occupation authorities, but not with the Austrians: they were happy to see Jews leaving, they were very worried by the prospect of them returning."

After the war Austria took refuge in an official narrative which portrayed the country as a "victim" of the Third Reich and avoided the process of debating complicity in Nazi crimes, as happened in Germany.

That meant not confronting the country's deep-rooted anti-Semitism. "I had to explain myself to ex-Nazi officials asking about my administrative status when I was deported," says Feingold.

What's more, "it was impossible to find a job. Someone coming back from the camps had to be a criminal. So I had to strike out on my own." He started a clothes shop in Salzburg which quickly became successful.

Feingold swore to himself in Auschwitz that he would tell his story and he has done so avidly. Despite his age, he takes part in numerous conferences and events for schoolchildren.

"I must have spoken to around half a million people all in all," he estimates.

And how does he see the current state of the fight against prejudice?

"Anti-Semitism is still there, even when people don't know why they're anti-Semites. But I think it is decreasing in the cities," he says.

In Salzburg, the Jewish community has dwindled from 600 members after the war to around 30 today. Feingold says that in the 1960s "many people emigrated because they thought there would be no place for their children in Austria."

However, he says the attitude of officialdom changed at the end of the 1970s: "Ever since that point I've been literally covered in honors," he says.

Another one is set to be bestowed on Feingold's 105th birthday, May 28, when he will be received by conservative Chancellor Sebastian Kurz and Vice-Chancellor Heinz-Christian Strache, leader of the far-right Freedom Party (FPOe).

Feingold says he was impressed by Kurz's speech marking the 80th anniversary of the Anschluss and adds he has "done more for the Jews that any of his predecessors."

Even though Strache and his party, which was founded by ex-Nazis, have been boycotted by Vienna's Jewish community, Feingold says he is looking forward to the occasion.