(JNS) In the Soviet Union of the 1970s, it wasn’t hard to meet Russians who knew the Communist system was incorrigibly corrupt, dysfunctional and oppressive. But it was one thing to whisper such truths to trusted friends, quite another to speak openly, to make oneself a target of the police state.

A member of the intelligentsia who kept his head down asked me this question: “What do you call a man of integrity in the Soviet Union?” When I shook my head, he dolefully provided the answer: “An inmate.”

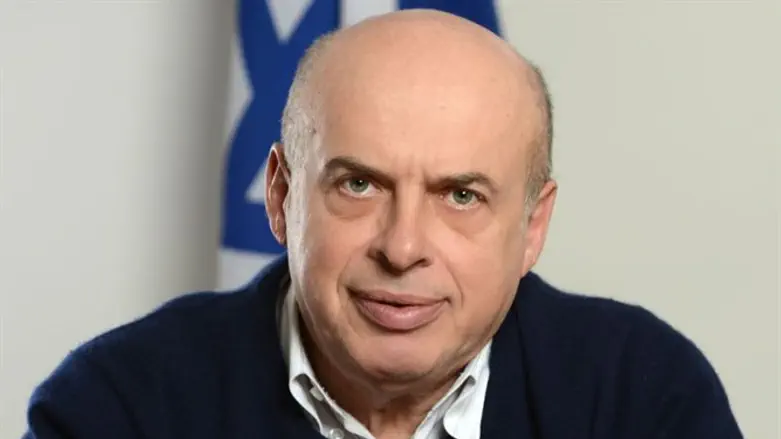

Natan Sharansky was born Anatoly Borisovich Shcharansky in 1948 in Stalino, a grimy Ukrainian coal town renamed Donetsk following the death of the second Soviet dictator in 1953. He showed enormous aptitude for mathematics and chess—useful pursuits for those who did not want to risk being “cancelled” (to borrow a contemporary expression) by the KGB. But he was not such a person.

In his 20s, he became a vocal Zionist (i.e. a believer in the right of the Jewish people to self-determination in part of their ancient homeland), refusenik (a Soviet citizen denied the right to emigrate) and human rights activist (not just for Soviet Jews but also for dispossessed Tartars, oppressed Pentecostalists, Armenian nationalists and others).

Before long, he was arrested, tried by a kangaroo court and, in 1978, sentenced to the Gulag. Released nine years later, he went to Israel where he spent nine years in politics, followed by nine years as head of the Jewish Agency, an organization that links Israelis with the remaining (or surviving) Jewish communities abroad.

He tells the stories of his life—along with large sprinklings of history, philosophy and polemics—in “Never Alone: Prison, Politics and My People,” written in tandem with Gil Troy, the eminent historian.

I had the opportunity to speak with Sharansky last week. I mentioned that I had attempted to report on his trial but, because it was closed to the press and public, the best I could do was hang around outside the courthouse with his supporters.

One day, a van arrived and backed up to the building’s exit. The van’s rear doors opened and then closed. The van drove away. We knew he was in it and where he was being taken.

Plaintively, his supporters called out what was then his nickname: “Tolya! Tolya! Tolya!” For more than 40 years, I’ve wondered: Had he heard them?

Sharansky told me he had not. But, emphasizing his book’s theme, he added that he had not felt alone or abandoned—not then and not during his years in captivity, not even during the long periods when he was confined to “punishment cells”—small, cold, dark cages with “no light, no furniture, nothing to read, no one to talk to, and barely anything to eat.”

Such sensory deprivation could drive one mad; indeed, that was what his jailers expected. He disappointed them in part by playing chess in his head—thousands of games.

When confined to a regular cell, he was allowed to read Pravda, and it was from that official Communist Party newspaper that he one day learned that President Reagan had called the Soviet Union an “evil empire.”

“I later discovered that his American critics condemned his speech as ‘the worst speech by a president, ever,’” he writes. “They claimed he had escalated world tensions by threatening a fellow superpower. For us prisoners, though, it was a great relief. It proved the real world was catching on and standing up to the Soviet liars.”

Upon his arrival in Israel, where he gave himself a more Hebrew name, he was embraced as a hero. Going into politics, however, did not increase his popularity.

He was close to Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin but strenuously disagreed with him over the 1993 Oslo Accords. Sharansky knew a thing or two about despotic regimes and was certain that bringing Yasser Arafat from Tunis and setting him up as Palestinian dictator would not lead to peace.

He also was close to Prime Minister Ariel Sharon but opposed his decision to unilaterally withdraw from Gaza. He was right again: Hamas went on to fight and win a war against the Palestinian Authority. It then transformed Gaza into a terrorist enclave. Ever since, most Israelis have understood that withdrawing from the West Bank in the absence of a peace treaty can only produce more bloodshed.

Sharansky did another nine-year stint as head of the Jewish Agency, focusing on what he calls the “ingathering of exiles,” bringing Jews to Israel from countries where they have been, at best, second-class citizens.

While still in the Gulag, he had read in Pravda about “Zionist soldiers” in Africa “kidnapping peaceful citizens, claiming they were Jews,” with the intention of incorporating them into Israel’s “insatiable military machine.”

Knowing how to decode Communist propaganda, he figured out what was really going on: A “long-lost tribe of fellow Jews” had been living in Ethiopia, mostly in rural villages, for more than a thousand years. They called themselves Beta Israel, House of Israel, but were more commonly known as Falasha, meaning strangers or wanderers, which tells you something about their status.

In 1991, he took part in a modern exodus—flying out of Africa with hundreds of Ethiopian Jews, some barefoot, most hungry, all eager to see Jerusalem and begin new lives. “Their very journey,” Sharansky writes, “was a psalm of rejoicing.”

He adds: “Here was one Am Yisrael, one people, returning to their land, whose applause, singing and African ululating merged into one impossible and triumphant symphony.” This, too, is true: Tolya from Stalino had come a very long way.

Clifford D. May is founder and president of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD), and a columnist for The Washington Times.