Total disavowal of life, as a lofty ideal of spiritual perfection, is acknowledged by many religions. Human consciousness is very impressed by a monastic and ascetic life of mortification and disconnection from the reality of this world. The mystique and aura associated with this lifestyle have caused many to think that it is the only way to reach intense spiritual heights. This might well be true. But the question remains: is this what is requested from us?

Actually, Judaism completely disavows the path of asceticism as a way of life for the masses and doesn’t even recommend it for the elite. The source for this is in our weekly Parasha which addresses, amongst other things, the topic of the Nazir. It finds expression in the writings of halakhic authorities throughout the generations, such as the great jurist and philosopher Maimonides, who also completely rejects this lifestyle as a way of life as he write in the Book of Love, Laws of Character, 3:1: “Lest a person say, ‘since jealousy, lust, glory, and the like are an evil path which destroy a person, I will completely withdraw from them and distance myself by going to the opposite extreme’ – to the point that he does not eat meat, drink wine, get married, live in a nice home, or wear decent clothing other than sackcloth, burlap, and the like, in the manner of pagan priests; this is also an evil path which it is forbidden to travel.

One who follows this path is called a "sinner”. (In his Guide to the perplexed he seems to glorify this way of life for the individual seeking elevation and the proximity of God.

This however requires careful analysis because you cannot say on one hand that it is a pagan conduct and on the other that it is a commendable one).

Our Parasha explains that the personal choice to be a Nazirite is, practically speaking, an agreement and resolution to avoid wine and grapes products, grow his hair and then shave it, and keep distance from impurity of the dead – no more than that. One who accepts this limited nazirism can feel that, on one hand, he is elevating and sanctifying himself, but on the other hand, that the Torah views him as a sinner because he rejects the principle of pleasures which have been given to him by God. In the times of the Temple, the Nazir was required to bring a sacrifice to atone for this sin.

Biblical Nazirism is not a commandment or expectation which pertains to the masses. It is recommended only for the exceptional individuals, who sense a need to behave differently for a period of time, in order to fix a blemish in their personal behavior. It is a tool for improvement and adjustment of one’s character, designed to generate balance and to inject new vitality into one’s life, full of energy and well channeled. Wine and drunkenness can invoke an onrush of negative forces. Avoiding them makes it possible for a person to refine and habituate himself with these subliminal positive forces. Growing one’s hair long and shaving it at the end of the Nazirite period expresses the idea that exterior beauty is unimportant, and that too much attention to externals can lead to egocentrism (like in the story of Rabbi Yohanan and the Nazir from the South). Distance from corpses teaches that the main focus of one’s attention should be to life and its processes, and not to the failure of life - death.

This limited Nazirism is no longer practiced. Nevertheless, we can still learn from it the degree to which we are expected to halt the flow of our lives in order to evaluate our behavior, especially with regard to anything pertaining to human relations and good character. This is expected of us in any context in life.

Whenever personal self-reflection shows us that there is room for improvement and correction, the proposed method is to tend a little bit toward the opposite extreme temporarily, in order to restore balance, alternately going from one extreme to the other in order to learn the harmony of the equilibrium between them. This is the ultimate goal is to return to the middle path, the golden mean. But – and this is essential – the golden mean is not as some thought it to be some kind of wishy-washy attitude of lukewarm morality. It requires the mighty strength of one who navigates with calm lucidity a razor sharp path through a jungle of dangers at the brinks of precipice in the most stormy inner weathers.

Even while one is a Nazir, while he undergoes a personal, inner process of education to improve his manners and behaviors, he is not expected to neglect family and social life, from acting and working for the greater good. In this context, two biblical figures stand out for having led and judged the people while they were Nazirites: Samuel the Prophet and Samson the Mighty. The Nazirism of Samson and Samuel lasted their entire lives and were harsher than the Nazirism described in the Parasha. Samson’s Nazirism was commanded by God while he was yet in his mother’s womb, and Samuel was a Nazirite by the wishes of his mother Chana. Nevertheless, they got along with others, led the Nation of Israel, fought wars, and worked for the greater good.

Building one’s personality while acquiring the habits of positive social behavior is a process which can last a lifetime, but when done consciously, paying attention to the integration of one’s personal development while being active and productive for society and state, in the manner of those leaders, then it might be expected that anything they touch will be that much greater.

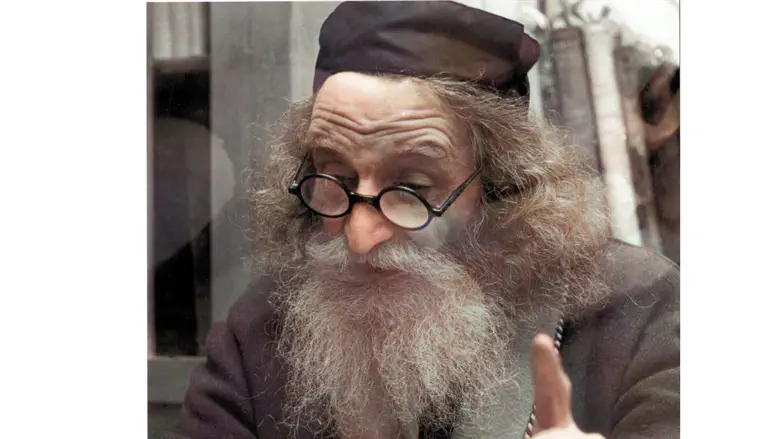

Rabbi Yeroham Simsovicwas Shaliach in Oxford (2006-2007) and is currently teaching at Yeshivat Horev in Jerusalem and the Garin Torani in Hertzeliya