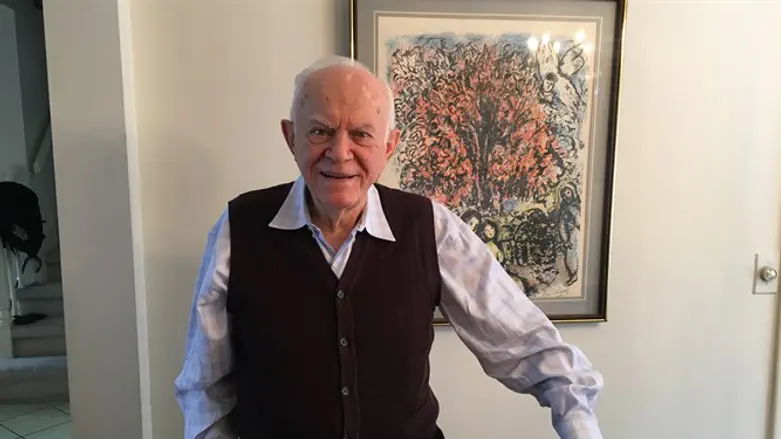

Mordechai Schachter didn’t know he would soon be a soldier when he traveled from his native Romania to pre-state Israel in 1948. He was a 17-year-old with a passion for Zionism, leaving behind a country that was becoming increasingly anti-Semitic a few short years after at least 270,000 Romanian Jews were murdered during the Holocaust.

At the end of 1947, Schachter had boarded one of two boats of 7,500 Jews each that were to take them to the promised land, despite a British ban on Jewish immigration there. Many of the passengers were lone children whose parents sent them on the boats to escape Romania. Schachter’s parents had meant to come, but his father fell ill before the trip, so they stayed behind.

The journey went as planned until the boats hit the Dardanelles, a narrow strait in northwestern Turkey. There they were met by seven British ships. Passengers decided not to fight back since a significant portion of them were children and elderly; their boats were rerouted to Cyprus. Three months later, the British agreed to allow the children, including Schachter, to go on to Palestine.

Schachter remembers arriving in Ra'anana, and eating hamentaschen and oranges on his first week there. In Ra'anana he also met one of his three brothers, who had arrived in pre-state Israel four months earlier. Five weeks later he was ordered to join the army, where he was taught how to shoot a gun and given an Italian rifle from World War I and 25 bullets. Others got “whatever they could find,” Schachter recalled.

“Everybody had a different type [of weapon] at that time. They had very little ammunition,” he told JTA on Monday at his home in this northern New Jersey township about 11 miles from Manhattan.

Schachter remembers the exuberance felt in Israel a few weeks later, on May 14, 1948, when the country declared its independence.

“Everybody was dancing in the streets celebrating,” he said.

The next day, a coalition of neighboring Arab states — Egypt, Syria, Jordan, Lebanon and Iraq — invaded the new country. Israel’s War of Independence would end the following year with an Israeli victory. Seventy years later, as Israel prepares to mark the milestone anniversary, Schachter spoke to a reporter about his role in Jewish, and world, history.

Schachter was assigned to be a mortar commander, which meant he did not have to be in the first line of fire. However, he had to deal with incoming mortars fired at him from the enemy side.

“We were in a couple of cases in very dangerous situations, but you don’t think about it because you are too young to realize how dangerous it is,” he said.

Schachter fought alongside native Israelis, immigrants from Romania, Poland, Hungary, Iran and Yemen, as well as volunteer fighters from the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

“It wasn’t easy for a commander to give orders,” he said. “Sometimes he had to give orders and somebody else had to translate the orders.”

One of his units had a large contingent of Yemeni Jews, so Schachter quickly learned how to communicate in Hebrew.

“We got very friendly because we fought together, so you’re like brothers,” he said.

When the war ended the following year (Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan and Syria each signed armistice agreements with Israel in 1949 between February and July, while Iraq did not sign an agreement), Schachter stayed in the army. Over 6,300 soldiers were killed as part of fighting during the war and several months preceding it, a number representing nearly 1 percent of Jewish settlers in Israel at the time. The Israeli army had over 100,000 Israeli soldiers by the end of the war, including 12 brigades.

After serving in the army for two years, Schachter took a job at a yeast production factory in Tel Aviv. He later studied television and radio repair at a school in Milan set up by World ORT, a Jewish organization providing education and training around the world. After four years in Italy, he returned to Israel, finding a job at a chemistry lab in Haifa and later a government computer center in Jerusalem.

Jerusalem is also where he met Fanny, the woman who would become his wife. At a party, the pair discovered that they both came from the same town in Romania, Botosani, in the northern part of the country.

Three months later, at Passover, Schachter went to visit his family, who by then had moved to America. They had survived World War II because Russia occupied Botosani right before its Jewish residents were set to be deported to concentration camps and were now living in the Bronx.

A month after Schachter arrived in the United States, his father died, so he decided to stay in New York and found a job working for a computer servicing company. He kept in touch with Fanny for a year via letters before returning to marry her in Israel and bring her with him to the US.

The couple would have two children and two grandchildren, relocating to Teaneck and joining Congregation Beth Sholom, a Conservative synagogue. Schachter, who still works part time for the same computer servicing company, says that although he does not consider himself “a hero,” he looks back at his time fighting in Israel with pride.

“You are proud of it,” he said. “You think you were there when this came up, and [that’s] something that doesn’t happen to every generation. Being there as a soldier, you feel happy, you feel good about it.”