Nathan Rosen’s favorite day in Hebrew class is culture day.

Every Friday, the students learn about one aspect of Israeli culture. Earlier this year Rosen, 13, did a presentation about Eli Cohen, the Israeli spy who infiltrated the highest echelons of the Syrian military in the 1960s.

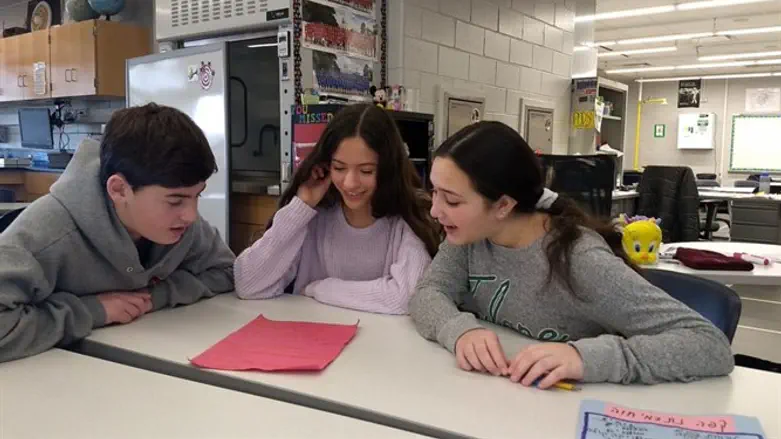

On a recent Friday, Rosen and two friends were working on a short Hebrew screenplay about a dysfunctional family that visits a cafe in Israel. The three eighth-graders huddled around a table, intermittently acting out the scene in loud voices and cracking up.

For Rosen, parts of the class feel similar to his former school, a private Conservative Jewish day school. But now he attends Alan B. Shepard Middle School, a public school in this Chicago suburb on the North Shore. Rosen plans to keep taking the language at a public high school in Deerfield next year.

More than anything, he loves the bonds it creates with his Hebrew classmates, all of whom are Jewish.

“We built a whole little community in the school,” Rosen said. “In the hallway sometimes, we’ll call each other by our Hebrew names, and it’s like no one else knows what we’re saying, but, like, we kind of feel like we have our own little relationships.”

Rosen is one of 680 students in the Chicago area studying Hebrew in public schools, according to the iCenter, a Chicago-based group that promotes Israel education. Excluding Hebrew language charter schools, approximately 1,400 students nationwide are studying Hebrew in public schools — and nearly half of them are in Chicago. Nine of the 22 American public schools that offer Hebrew are located in the Chicago area, according to a new report from the Consortium for Applied Studies in Jewish Education. Others are in Minnesota, Ohio, Texas, New York and elsewhere.

Most American students who study Hebrew daily do so in Jewish day schools. A substantial number — in New York, Florida and elsewhere — also attend Hebrew-language charter schools that integrate Hebrew throughout the day. But a growing number of students are studying the language in traditional public schools.

Chicago’s public school Hebrew enrollment has jumped by more than a third in three years, from some 500 in 2016 to 680 today, according to the local Jewish federation. CASJE — a group of academics, teachers and donors working to improve the quality of Jewish education — says the numbers of public school Hebrew students are growing nationwide as well.

Public school Hebrew classes are broadly similar to other public school foreign language instruction. But Jewish parents and local Jewish community leaders appreciate them because they provide students with another link to their Jewish identity. The vast majority of students in the Chicago programs are Jewish, teachers say.

“Here they get to be with Jewish students one period every day,” said Helene Herbstman, whose daughter studied Hebrew in public school and who helped recruit other parents to the Hebrew programs on behalf of the local Jewish federation. “The content was more about Israel. You’re learning how to speak conversational Hebrew. You come out of these bar mitzvah programs [at synagogues], you’re not speaking Hebrew.”

Chicagoland high schools have had Hebrew programs since at least the 1970s, but the number of schools has increased in recent decades thanks largely to the efforts of Peter Friedman, a longtime local Jewish federation executive who died earlier this year. Friedman and Herbstman surveyed area synagogues asking whether parents would support Hebrew programs at their local schools and then encouraged those parents to lobby their school boards for the programs.

Now seven high schools in Chicago suburbs with large Jewish communities offer Hebrew, the largest being Deerfield High with approximately 180 Hebrew students. Last year, two Deerfield middle schools also began offering Hebrew. One high school appears to be phasing out the program.

Anne Lanski, founder and CEO of the iCenter, which holds professional development classes for Hebrew teachers, said public school Hebrew took off in the area because the vast majority of the city’s Jewish high schools are Orthodox, leaving much of the Jewish community looking elsewhere for Jewish enrichment.

“We didn’t have a high school that wasn’t Orthodox for most of our time,” Lanski said. “So the kids who wanted to continue with some engagement provided an audience” for Hebrew classes.

In addition to reading, writing and speaking, classes teach about Israel. In Rosen’s class at Shepard Middle School, students play Taki, an Israeli version of the card game Uno, and learn Krav Maga, the Israeli martial art. Niles North High School, in the historically Jewish suburb of Skokie, has an exchange program where students go to Israel for 10 days and welcome a visiting Israeli contingent to their school.

“It’s not just about a language — it has to be connected to a land and people,” said Yaffa Berman, who has taught Hebrew at Deerfield High for eight years. “We have to invigorate the language in a way that makes it cultural. It has to have an experiential part to it. It has to tell a story.”

Teachers avoid addressing the Israeli-Arabconflict directly, though they do discuss the Israel Defense Forces and Israel’s domestic politics. This year, the Shepard class learned about Israeli elections and the two leading candidates. They have also learned about the standard IDF uniform and the force’s different divisions. One high school class studied Israel’s 1976 hostage rescue operation at Entebbe Airport in Uganda.

“[After Yitzhak] Rabin’s assassination, every kid came to class just waiting, and knowing that there was nowhere else” to discuss the news, said Lanski, who used to teach Hebrew in a Chicago public school. “They knew when they got to Hebrew, they could talk about it and learn about it.”

Since Hebrew is the official language of Israel and Israel is the Jewish state, teaching the language inevitably involves broaching Judaism, which requires something of a balancing act in a public school. To abide by public school guidelines, teachers keep the discussions focused on the cultural. Berman, for example, gave her students sufganiyot, the jelly doughnuts traditionally eaten on Hanukkah, but did not light the menorah or say a blessing. Lichtenfeld has to remind kids not to ask questions about their bar mitzvahs or bat mitzvahs in class.

But Sharon Avni, who co-wrote the CASJE study with Avital Karpman, said that every language class encounters some kind of cultural-religious tension.

“Religion happens in public school all the time,” said Avni, a language and literacy professor at the City University of New York. “If you go into Spanish class, they might talk about a holiday that’s celebrated, and it’s very much related to the Catholic Church. I’m not necessarily saying they’re doing Jewish [in Hebrew class], but it’s not like religion doesn’t happen in public schooling.”

Advocates of public school Hebrew aren’t worried about the lack of explicitly religious content. For them, it’s enough that students have one period a day where they’re connecting to the language — and each other.

“What’s important about Hebrew is, you’re staying connected to the Jewish community,” Herbstman said. “With less and less people belonging to synagogue, and more and more families dropping out of synagogue after bar mitzvah, this is the one connection your child will still have with Israel.”