Michael Slominsky was a Shaliach in Montreal (2023-24)

Parashat Mishpatim is one of the most packed portions in the Torah. It details numerous mitzvot and laws that relate to almost every aspect of life. These laws appear between the section of Matan Torah, which we learned about last week in Parashat Yitro, and the covenant between Hashem and the people of Israel, which is recorded at the end of our parasha.

Our parasha begins with the words "And these are the laws" (ואלה המשפטים). The letter "Vav" at the beginning seems unnecessary—if the Torah is introducing a new topic and new laws, why is there a need for a conjunction? The sages already addressed this question and explained that the purpose of this "Vav" is to connect these laws to Har Sinai, teaching us that just as the Ten Commandments were given at Sinai, so too were all the laws and judgments in our parasha.

Throughout history, people have often been drawn to the "big" and dramatic aspects of Judaism—events like the revelation at Mount Sinai, the Ten Commandments, and at the end of our parsha, the covenant between Hashem and the Jewish people. However, when it comes to the smaller details, such as the laws found in Parashat Mishpatim, it has often been harder to feel that same connection. From this perspective, it might seem preferable to skip over the "smaller" mitzvot among the 613 and go straight to the ones that seem greater and more important.

Examples of this phenomenon can be found in several places: The Gemara in Berachot records that in some places, people wanted to establish a reading of the Ten Commandments alongside Keriat Shema. However, this was ultimately abolished "because of the claims of the heretics" (בטלום מפני תרעומת המינים).

The commentators explain that this was done to prevent the mistaken belief that only the Ten Commandments were given to Moshe at Sinai, while the rest of the Torah was not, thereby leading people to consider them less important.

Additionally, this idea is at the root of the debate regarding whether one should stand during the public reading of the Ten Commandments. Those who argue against standing do so to prevent any one part of the Torah from being given precedence over another.

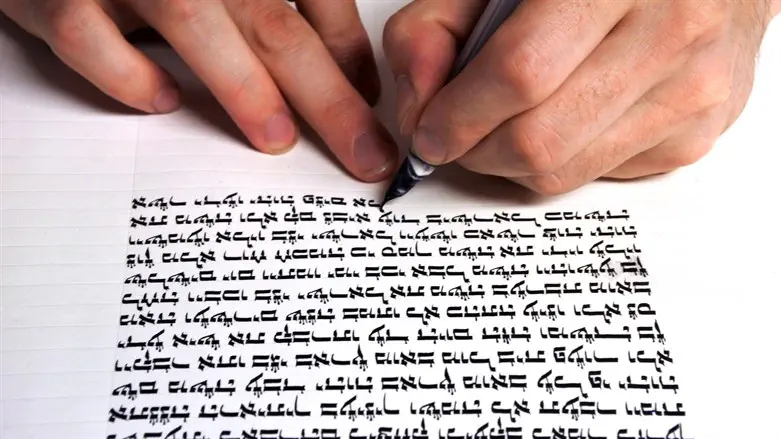

Even today, it is easier and more pleasant to speak about spiritual peaks, about lofty divine connection, rather than about practical mitzvot that require effort—such as "You shall not go about as a talebearer among your people" (לא תלך רכיל בעמך) or "You shall not take revenge nor bear a grudge" (לא תקם ולא תטר). Indeed, the laws of Mishpatim are not simple at all. Many of the most difficult and intricate Talmudic tractates are based on just a few verses from our parsha and nothing more.

In reality, however, the Torah teaches us that small actions and seemingly insignificant laws are just as important. These laws were given to us so that we could establish a just, wise, and caring society. Walking this path is what ultimately leads to spiritual elevation and closeness to Hashem. However, and perhaps this is precisely why, the journey is just as important as the peak. Without the journey, one cannot truly reach the summit.

This principle is also evident in Moshe’s leadership in Parashat Yitro. There, the Torah describes how "Moshe sat to judge the people from morning until evening" (שמות יח:יג). One might have expected Moshe Rabbeinu to spend all his time engaged in divine revelation and prophecy. However, the Torah shows us that instead, Moshe was deeply involved in legal disputes among the people—likely not always about matters directly connected to divine connection, but rather about social and civil issues. From morning until evening, Moshe dealt with these concerns until Yitro approached him to question his approach.

When Yitro confronted Moshe about his actions, Moshe responded: "Because the people come to me to seek God" (שמות יח:טו). For Moshe, there was no separation between being a man of God and resolving disputes between two individuals arguing over a minor issue. The great sages of Israel throughout the generations followed this example—investing much of their time in addressing practical halachic questions that affect everyday life, rather than engaging only in lofty spiritual discussions about divine connection.

In our Torah, there is no division between the philosophical and the practical—between divine closeness and building a just and moral society. The majority of discussions in the Talmud revolve around issues that sometimes seem small and unimportant, but they are all part of a greater legal system that ultimately strives to create a nation seeking perfection.

The Ten Commandments in Parashat Yitro and the laws and judgments in Parashat Mishpatim are, in essence, one unit. At the end of our parsha, when the covenant is established between Hashem and Israel, Moshe presents to the people "all the words of Hashem", referring to the Ten Commandments, but also "all the laws", referring to the laws of our parsha. The people respond "in one voice", declaring: "All the words that Hashem has spoken, we will do" (שמות כד:ג). The covenant is established through both aspects—the "big" revelations and the "small" laws—together leading to spiritual heights.

In our time, frustration and helplessness often arise when thinking about the situation in Israel. Many of us ask: What can we do for our country and for our people? How can we contribute? Sometimes, it feels like our actions have little impact—most of us do not hold high positions of influence, and this only increases the feeling of powerlessness. But from what we have learned, this is not true.

Our good deeds, even the smallest ones, create a profound and far-reaching impact, much like the countless inspiring social initiatives that have emerged since the war began, bringing immense support and healing to our wounded nation.

May we hear good news.